Year:

Duration:

Recorded:

Pagan Paean 35 years later…

“Hey Chuck, we got some non-believers out there.”

Flavor Flav – Public Enemy – Timebomb (1987)

I started filming Pagan Paean in July 1990 and finished it about a year later.

This text is an edited and extended version of the text which I wrote for the catalogue of my exhibition – ∞ : a Selection of 8 Videos – at Warren Siebrits Modern and Contemporary Art in Johannesburg in 2004.

Pagan

The etymology of the word – pagan – is of key importance to the main thrust of this film.

It is derived from the Latin word paganus – originally meaning – villager or rural person.

In Roman military jargon, paganus also meant – civilian – in the sense of – non-soldier, or incompetent soldier; which early Christian authors like Tertullian and Augustine used to metaphorically contrast with the word – milites – soldier – as in “soldier of Christ”.

To summarise – pagans were rural people, or those who weren’t “soldiers of Christ”.

In Victorian times, philologers such as Richard Trench held the view that since Christianity had first found a foothold in towns and cities – while rural people clung to the old religions – they called non-Christians – pagans.

In my view, this is justified, because the word – heathen – is also thought to be derived from the German word Heiden – which could mean – one living on the heath ie: uncultivated land.

So, we have a dichotomy between the ‘modern’, ‘true believer’, city slickers – versus – the ‘old school’, country bumpkins . 1

But what belief – am I talking about?

Twenty-one years ago, when I first wrote this text, I said that this film is about systems of power – both visible and invisible – and the influence they have on a landscape and its inhabitants.

Looking at it now, I would say that this film is more specifically about knowledge- and belief systems, and the power imbalances between the adherents of those systems.

Certainly religion is one manifestation of a belief system, but I also include science and socio-political dogma – from the point when people start believing in the infallibility of a system.

Human cognitive processes, and our various languages, are all abstract constructions of signs and symbols, which allow us to analyse, evaluate, and reframe situations. They allow us to gain insights, and to build the complex and powerful tools and systems that we use.

But it is important to realise that – inherently – all such symbolic systems 2 , or models, are based on the simplification of fantastically complex natural processes.

Nonetheless, they often magically seem to work. And often these simplified, idealised models become so reassuring, that we start believing that they represent Reality.

Opening with a shot of a telephone mast and cables, followed by electricity pylons – part of the country’s power grid – the film also features a road, a railway crossing and fences – all the classic tools for ‘civilising’ 3 an ‘untamed’ land.

While superficially quite benign or beneficial, the introduction of any one of these elements has far-reaching – often unintended – consequences on the existing social and natural landscape.

On a more abstract level, but equally important to the world-view which has subjected most of the world using the above-mentioned infrastructure; is the superimposition of a linear 4 , ever-ticking, Time – referred to by the use of time-lapse recording and the ‘speaking clock’ in the soundtrack.

This particular conception of time is often imbued with a pernicious combination of Darwinism and technological development: The notion that, with every technological development, we are one step further away from our ‘primitive’ origins – that we are becoming cleverer and cleverer.

It is impossible for this world-view not to view with disdain, or smug paternalism, cultures with different attitudes towards technology and time – even our own ancestors.

This is a culture which takes its clever maps and models of the world, to be the world.

A culture which has relativised or idealised to abstraction, every Thing, every Truth.

Where people have become statistical composites and the body is viewed as an unfortunate glitch, or remnant, as the age of enlightenment reaches light-speed.

This makes it possible for the crew of an Apache helicopter gunship, surveying the landscape through infra-red sensors, to laughingly follow the little human figures scurrying around on (the dead blackness of) their screens, train green crosshairs on them, and “spray and slay” them with all the detachment of a computer game. The Desert Storm 5 smart-bomb images in the film now look positively ‘old-school’, FPV Drones are the current new thing apparently.

Opposed to this worldview, there are those figures in the landscape – the pagans – the man patiently collecting maize kernels and cobs missed by the combine harvester – to plant them on a small patch of land, graciously allowed by the land-owner. The boy and his three dogs, hunting hares for the pot – eking out an existence. The grieving farmers, living near Chernobyl 6 , mourning the radiation death of their daughter – both of them probably long-dead by now. The dachas and villages deserted by the same nuclear apocalypse…

And as the Roentgen count increases, the stag turns away from camera to face death in an unmediated forest at the end of the world…

This was the end of my previous text, written in 2004.

Figures in a landscape revisited:

In the text above I mention the two figures 7 whom I filmed as they crossed my path in the expansive landscape. I paint them with a political, Marxist brush – which certainly – in the context of South Africa in 1990 – is a valid approach.

However, considering the videos I’ve subsequently made; and insights I’ve gained during the intervening thirty-four years; I would like to offer another view.

I have always loved generic descriptions of paintings, like: Still-life with Flowers, View from a Window, Interior with Figure, or indeed – Figures in a Landscape.

This happens either because little is known about the work or the artist – with little provenance or biography to assist the historian… or because it is simply a generic – everyday – scene . 8

This is definitely not a “Napoleon crossing the Alps” – there is no drama, no heroes, no grand narratives, no historic triumphs… just everyday scenes like: Man collecting Maize Cobs, or Boy with Dogs Hunting Rabbits; or Hunter standing by Pond… quaint – or rural – as they might sound.

But there is nothing sexy about these scenes. They present the polar opposite of our modern, technology-saturated lives – drowned and distracted by the sensational, clamouring, over-hyped flim-flam media machine – where everything is beautiful, superficial or artificial, and nothing is real.

Small wonder we begin to lose all empathy, our “humanness” – our humanity – despite spending all our time on “social” media – sharing pet videos, ever-so-witty memes, and being whipped into frenzies by all kinds of injustices – apparently perpetrated in far-flung corners of the world where we have never actually been.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not some technology-hating luddite.

But I do feel we need to be very, very aware of the effect that the technology itself – not just the content – has on us.

As Marshal McLuhan used to say: The Medium is the Message.

Just like a simple road, or power-line, causes profound and far-reaching changes to the societies and landscape where they are built.

For every new technological tool we acquire, we lose a skill, or power we have in ourselves – we become weaker.

We might now be able to do something quicker, or faster, or more powerfully; but we fundamentally start losing, or forgetting the original ability or skill we had.

It is a zero sum game – you gain one, you lose the other.

This seemingly unstoppable process is currently reflected in the insane clamouring for so-called – Artifical Intelligence – where people are seemingly yearning to relinquish the last thing which defines Homo Sapiens – our ability to reason – to the machine.

We live in a world where governments are being swept up by trans-national tech companies, taking over all functions of government and installing all forms of control.

A technology cult of atheist, tech-supremacists, preaching trans-humanism – the absolute height of misanthropy.

But the day will come 9 . The day the much-vaunted techno miracle machine grinds to a halt. And we end up with empty shelves and empty selves – because we have relinquished all natural abilities, externalised everything – given everything – even our memories and reasoning for the machines to look after, or to do.

As some character in an imaginary Ridley Scott movie might say: “You use a droid, you become a droid.”

In contrast to all of this – paraphrasing Matthew 5:5 – “Blessed are the pagans, for they will inherit the earth.”

Because the despised pagans – with anti-hubristic humility – will be singing: “Lord have mercy on me” – acknowledging that they are not masters of the universe – not wise guys – and sing paeans by firelight.

Anecdotes and Comments on the Making of Pagan Paean:

All the landscape scenes in this film were shot in the Southern winter of 1990, near a place called Boons, in – what was then called – the western Transvaal, South Africa. I had first discovered this landscape the year before, on a shoot with Reinhold Cassirer. 10

When we came back the following year, I brought my 8mm camera with me. Driving back to Johannesburg in the late afternoon, Reinhold saw a pond with tall trees growing next to it. He suggested we stop to see if there were any ducks around. He walked over to the pond with his beloved Weimaraner – Bodo – and his trusty Purdey shotgun in hand. I started filming the scene as dusk approached. All the shots around the pond lined with tall trees including the boy and his dogs, were filmed that afternoon. When I received the newly scanned 4K file of the film in early 2025, I was totally blown away to discover that I had actually recorded Reinhold and his dog Bodo standing under the trees by the pond. It was the first time I had ever noticed him because of the size and quality of the scan. He thus became the third Figure in a Landscape.

Inspired by the stark beauty of highveld winter landscape; I returned the next weekend for more filming – this time with my friend Warren Siebrits to keep me company. All the remaining landscape shots – including the fire scenes – were filmed on that day.

All the television images were filmed from VHS recordings that I had made following the Chernobyl disaster and the Gulf War which started at that time.

In those days, there was no possibility for me to add a soundtrack to the edited 8mm film master. The only affordable option was to have the film copied onto VHS and then to dub the soundtrack onto the tape. The dub was done by Vijay Ramnundlall in Johannesburg.

Pagan Paean turned out to be the last film I ever made. Around the end of 1991 I bought by first S-VHS camcorder, and embraced video.

Footnotes:

1: The late Bruce Chatwin saw in the story of Cain and Abel, the story of the Settler, or City Dweller, killing the Nomad, or Itinerant, living off the land. A notion certainly germane to this train of thought. (return)

2: Which are essentially analogies, metaphors or symbols representing relationships. (return)

3: Please note that the word civilise is related to the word city. (return)

4: It is important to note that there are two broad conceptions of time, adhered to by different cultures and traditions. On the one hand we have a linear, ever-extending, ‘arrow’ of time – where you start at point A on a straight line, and end at point B – further along that line.

On the other hand, we have an ever-repeating, ‘wheel’ of time – where you start at point A, and after a certain while, come past point A again – an endless cycle. This idea certainly doesn’t fit notions of ‘progress’. It’s also worth considering that farmers and those living closer to the land, are much more aware of the annual cycle of seasons… that ever-turning wheel. While on the subject of time; I must say that: Real, lived time, is also much slower than the “reel” time of mediated, edited, virtual life. (return)

5: The 2nd of August 1990 saw the start of Operation Desert Storm. An important catalyst in the creation of this film. (return)

6: While on the subject of catalytic events which engendered this film, I must mention the nuclear reactor meltdown at the Chernobyl power station on the 26 of April 1986. It was an event that shook to the core, my youthful, naïve, positivist believe in technology and the promised benefits of science. (return)

7: To my astonishment and great happiness, I discovered a third figure in the landscape after I had the film scanned in 4K resolution. More about this later. (return)

8: There are certainly beautiful exceptions to generic descriptions. My favourite being: Landscape with Man Killed by Snake. (return)

9: When fire, or earthquake, or sequence of unforseen events brings the house of cards tumbling down. In the Greek myths, the gods always mercilessly punish hubris – like Icarus, Arachne, Sisyphus, Phaeton… the list is long. (return)

10: I had known Reinhold Cassirer and his wife – Nadine Gordimer – since my early teens. We had gone on many shoots over the years; spending weekends on farms all over the Western Transvaal – as it was then called. He was a supremely cultured man who had a big influence on my life. (return)

Post Script

This film was the fourth in series of films that I made between 1986 and 1991. Their DNA is very similar in the sense that they were created during a very intense period of South Africa’s recent history. To date, my first film is also available in this archive. In case you’re interested, follow the following link:

I love the smell of burning dust (1986)

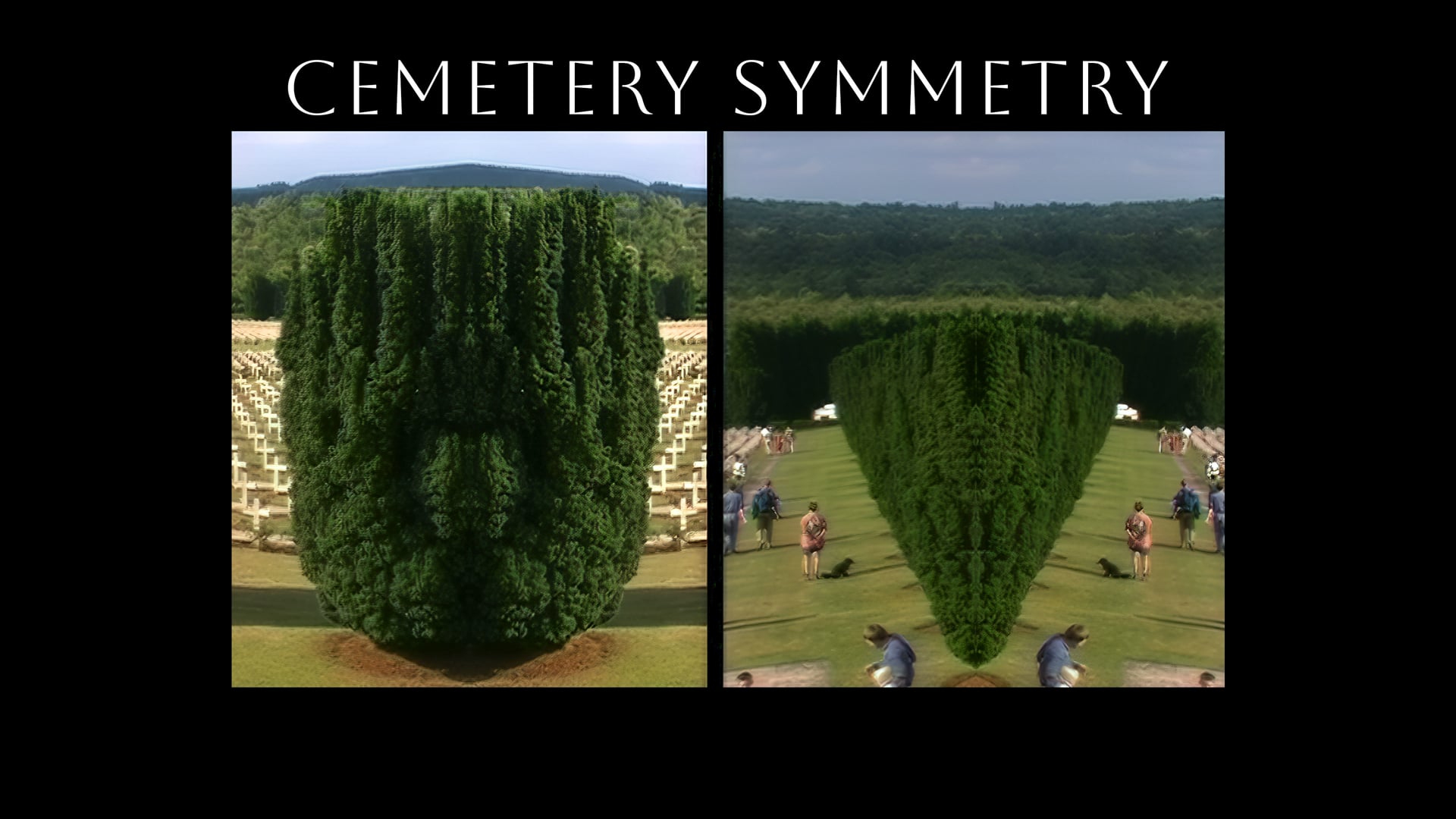

Like Pagan Paean, another work of mine which addresses the dehumanising, misanthropic nature of technology is:

Bachelor Machines (2010)